Attack of multi-armed bandits

This post is part of my struggle with the book "Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction" by Richard S. Sutton and Andrew G. Barto. Other posts systematizing my knowledge and presenting the code I wrote can be found under the tag Sutton & Barto and in the repository dloranc/reinforcement-learning-an-introduction.

Multi-armed bandit problem (or k-armed bandit problem) is one of the reinforcement learning problems, I don't know if it's the simplest one, but it allows for a relatively quick introduction to the subject and to become familiar with the basic concepts.

Let's imagine that we are in a casino and we are playing on a dozen or so one-armed bandits. Slot machines are different. For pulling the lever in some of them we can get a bigger reward than in others. The reward we can receive is from a certain probability distribution, sometimes larger, sometimes smaller. For now, we assume that the distribution does not change over time. Our goal is to find a slot machine with the highest accumulated prize value. We have to spend some time looking for a good machine, but we want to use the most optimal one as quickly as possible.

The above example with slot machines is, of course, quite artificial. Multi-armed bandit in practice can be used for things such as:

- clinical trials - to find the most effective experimental therapy and minimize the negative effects of these weaker therapies on patients.

- investment portfolio management - to find the best strategy for our investment portfolio.

- instead of A/B tests - to reduce conversion losses, in A/B tests traffic is divided equally, regardless of how each version of the website performs. In MAB the movement is gradually changing towards the best version.

Epsilon-greedy strategy

Ok, let's start with the simplest strategy for solving MAB, which is the -greedy strategy. What we are looking for is the so-called action value. Let us denote the action selected in step as and the corresponding reward as . The value of the selected action, denoted as , is the expected reward (average of rewards) when action is selected:

If we knew the value of each share, we could easily solve MAB, just choose always the share with the highest value. However, we do not know these values, we need to estimate them. We denote the estimated value of action at time as . At each time step there is at least one action that has the highest value. If we choose another, worse action, we explore. In the short term, we lose by performing this worse action, but we hope that in the long term we will accumulate a greater cumulative value of rewards if it turns out that one of these worse actions is better than the current best one. By accumulating knowledge about the value of rewards for each action, we become more and more convinced which action is the best by exploring and using the knowledge we have already acquired. An interesting issue is when and how often to explore and use the acquired knowledge. The simplest method uses a predetermined value of . At each step, with probability , we choose the best action (knowledge exploitation phase, exploitation). We select the best action by simply calculating the simple arithmetic average of the accumulated prizes for each action separately and selecting the one with the highest value. However, with probability , exploration takes place, during which we randomly select any action. Regardless of whether we explore or not, we save the received reward assigned to the selected action.

Time for the code

I don't know if I described everything clearly above, but I think the code should clarify the matter more. The following example contains a Bandit class that executes -greedy strategy for the three parameters given in the constructor. We can set the algorithm for how many actions, for how many time steps and for which epsilon. The constructor also initializes the true_reward variable with random values, and then, when the algorithm is executed, the rewards are returned with the true_reward value plus some noise (to make things easier). The whole essence of -greedy strategy is contained in the choose_action method. There, exploration/exploitation of knowledge takes place with the help of epsilon.

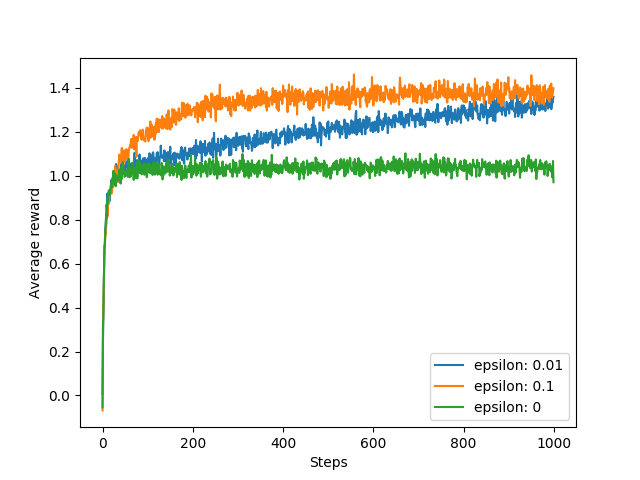

The main code (under __main__) contains an example of a single run of the algorithm and, perhaps more interestingly, a comparison of three different values of (0, 0.1, 0.01). I performed 2000 runs for each of them and averaged the results, so you can see in the chart below what the average rewards look like for a given epsilon depending on the number of iterations.

You can see that for a value of 0.1, the optimal action is found quickly, but will never be selected more than 91% of the time. For a value of 0.01, the optimal action is found more slowly, but in the long run it will achieve better average results.

Okay, here's the code:

'''

Multi-armed bandit with e-greedy strategy

With saving all rewards for each arm

'''

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from random import randint

import random

class Bandit:

def __init__(self, arms, pulls, epsilon):

self.arms = arms

self.pulls = pulls

self.epsilon = epsilon

self.history = []

# random values from normal distribution

self.true_reward = [np.random.randn() for _ in range(self.arms)]

self.rewards = [[] for _ in xrange(self.arms)]

def get_means(self):

means = np.zeros(self.arms)

for index, action_rewards in zip(range(len(means)), self.rewards):

if len(action_rewards) > 0:

means[index] = sum(action_rewards) / len(action_rewards)

return means

def choose_action(self):

rand = np.random.uniform(0, 1)

# select action with 1 - epsilon probability

if rand > self.epsilon:

# exploit

means = self.get_means() # compute all means

argmax = np.argmax(means) # select arm with best estimated reward

return argmax

else:

# explore

return randint(0, len(self.rewards) - 1)

def get_reward(self, action):

return self.true_reward[action] + np.random.randn() # true reward with noise

def save_reward(self, action, reward):

self.rewards[action].append(reward)

def run(self):

for t in range(self.pulls):

action = self.choose_action()

reward = self.get_reward(action)

self.save_reward(action, reward)

self.history.append(reward)

if __name__ == '__main__':

# example bandit

bandit = Bandit(arms=10, pulls=2000, epsilon=0.01)

bandit.run()

for arm, reward, true_reward in zip(range(1, len(bandit.rewards) + 1),

bandit.rewards, bandit.true_reward):

pulls = len(reward)

print "Arm {} pulls: {}, true reward: {}". \

format(arm, pulls, true_reward)

print "Best arm: {}".format(np.argmax(bandit.true_reward) + 1)

# experiments

pulls = 1000

experiments = 2000

epsilons = [0.01, 0.1, 0]

mean_outcomes = [np.zeros(pulls) for _ in epsilons]

for _ in range(experiments):

for index, epsilon in zip(range(len(epsilons)), epsilons):

bandit = Bandit(arms=10, pulls=pulls, epsilon=epsilon)

bandit.run()

mean_outcomes[index] += bandit.history

for index, epsilon in zip(range(len(epsilons)), epsilons):

mean_outcomes[index] /= experiments

plt.plot(mean_outcomes[index], label="epsilon: " + str(epsilon))

plt.ylabel("Average reward")

plt.xlabel("Steps")

plt.legend()

plt.savefig('01_plot.png')

Sample output:

Arm 1 pulls: 3, true reward: -0.903469191365

Arm 2 pulls: 3, true reward: 0.365839293594

Arm 3 pulls: 3, true reward: -0.854871239295

Arm 4 pulls: 2, true reward: -0.445679248867

Arm 5 pulls: 94, true reward: 1.0921733926

Arm 6 pulls: 3, true reward: -0.123881634804

Arm 7 pulls: 0, true reward: -0.928756860211

Arm 8 pulls: 5, true reward: 0.860238065648

Arm 9 pulls: 1885, true reward: 1.81443343678

Arm 10 pulls: 2, true reward: 0.247351866388

It's not always rosy:

Arm 1 pulls: 1244, true reward: 0.865701931312

Arm 2 pulls: 1, true reward: -0.0986266557818

Arm 3 pulls: 2, true reward: -0.93574271516

Arm 4 pulls: 4, true reward: 0.273764997199

Arm 5 pulls: 2, true reward: -2.24599693076

Arm 6 pulls: 3, true reward: -0.0837555511977

Arm 7 pulls: 208, true reward: 0.679058209084

Arm 8 pulls: 2, true reward: -0.983193383821

Arm 9 pulls: 2, true reward: -0.0941783631123

Arm 10 pulls: 532, true reward: 1.78310799226

Summary

I presented the simplest strategy for solving the multi-armed bandit problem known as -greedy strategy. Of course, there is much more. You can imagine the value of decreasing over time, an algorithm with an exploration phase first and then using the acquired knowledge, and many, many other strategies. But more on that in subsequent posts.